Youth soccer coaches are the foundation of youth sports development, guiding thousands of kids through their first experiences with teamwork, discipline, and confidence. These dedicated mentors do far more than run practices or manage games—they shape environments that influence whether young athletes stay in the sport and learn lifelong values. Understanding their role and how parent support in soccer can strengthen it is key to building a healthier, more positive youth soccer culture.

Youth coaches are the quiet engine of the game in this country. They rarely coach for money or recognition; most step onto the field because they love soccer and feel called to guide young people during some of the most important years of their lives.

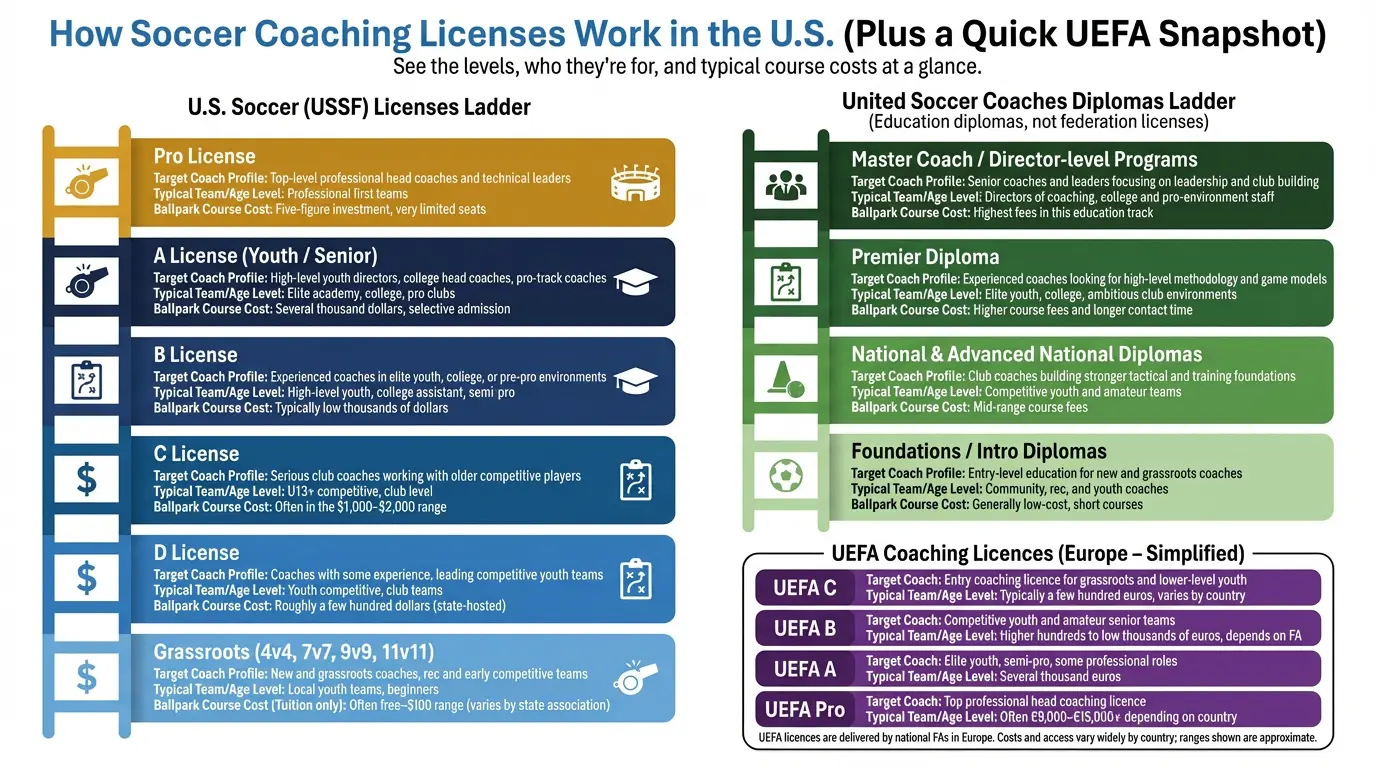

A quick snapshot of youth coaching

Before diving deeper, it helps to see a few “snapshot” facts that capture the landscape of youth coaching today. These are not the whole story, but they frame what many families don’t see.

Seen together, these numbers describe a role that is emotionally demanding, modestly compensated, and yet deeply driven by purpose.

Most youth coaches start for reasons that have very little to do with a paycheck. The dominant motivations are a deep love of the game, a desire to give back, and a genuine interest in mentoring kids. Many are former players who miss the rhythms and relationships of soccer, and coaching gives them a way to stay connected to that part of their identity.

Others are driven by their own childhood experiences—good or bad. Some had a great coach who changed their life and want to offer that same steady presence to a new generation. Others remember an environment that was overly harsh, disorganized, or transactional and feel compelled to build something better for today’s kids. In both cases, the motivation is rooted in a belief that sport can and should be a positive, formative force.

Research on youth sport consistently shows that coaches play a central role in whether kids feel confident, enjoy their sport, and choose to stay involved. When a coach creates a supportive, mastery-focused environment—one that values learning and effort as much as results—players are more likely to stick with the game and carry those lessons into other areas of life. Many youth coaches understand this intuitively, and that sense of impact is a big part of why they keep showing up.

Not all youth coaching roles look the same. The expectations, qualifications, and compensation vary significantly from recreational programs to the highest tiers of competitive youth soccer.

At the recreational level—local town leagues and community-based programs—coaches are often volunteers, frequently parents who step up because no one else did. Formal licenses may be encouraged but are rarely required, and organizations typically provide short clinics or age-specific guidelines to help new coaches get started. Duties center on creating a safe, fun environment: organizing simple practices, rotating positions, and making sure every child gets meaningful playing time. Compensation, if any, usually takes the form of small stipends or discounted player fees rather than a true wage.

In developmental and lower-tier competitive club settings, coaches may be a mix of volunteers, part-time paid staff, and young coaches starting out. Some clubs begin to require entry-level coaching licenses and background checks, especially if they are affiliated with larger state or national bodies. These coaches are expected to design more structured practices, introduce team concepts, and manage communication with parents about schedules, basic expectations, and player progress. Pay might range from modest per-session or per-team stipends to limited seasonal contracts, but it is rarely enough on its own to support a family.

At the higher tiers of club and “elite” youth soccer—travel teams, regional leagues, and national-platform clubs—coaches are more likely to hold advanced licenses and have years of experience. Clubs at this level often hire staff coaches whose responsibilities span multiple teams, age groups, and programs. Duties extend well beyond training and match day: they include player evaluations, individual development plans, college guidance, extensive travel, tournament management, and regular meetings with directors and technical staff. Compensation can reach into full-time territory, especially when combined with camps and supplemental training, but even then it often sits in the range of 30,000 to 60,000 dollars a year depending on region and club size—hardly extravagant given the hours and weekend commitments involved.

Across all levels, the through line is that the paycheck lags behind the responsibility. Whether they are volunteers or professionals, youth coaches are being asked to juggle development, safety, communication, and culture in increasingly complex environments.

From the stands, coaching can look like a couple of practices a week and a game on the weekend. In reality, responsible youth coaches are putting in hours that most families never see. Practice does not start when the kids arrive; it starts when the coach sits down to plan age-appropriate activities, progressions, and small-sided games that match the group’s needs.

That planning has to be flexible. Coaches review how the last session went, think about which players need extra support, and adjust for who is injured, who is struggling, and what the team is ready to tackle next. The best youth coaches are constantly learning: they read, watch sessions online, attend courses when they can, and talk with other coaches about what works.

Then there is the emotional and relational work. Youth coaches manage playing-time conversations, team chemistry, and the expectations of numerous families, each with their own hopes and worries. A national survey highlighted that parent conflict, toxic sidelines, and late-night complaints are among the primary stressors driving coaches toward burnout and, in some cases, out of the game entirely. That kind of responsibility does not disappear when they leave the field; many carry it home and think about it long after the game is over.

Administrative tasks add another layer. Coaches juggle schedules, communicate about games and tournaments, organize travel, and handle paperwork. In many clubs, especially at younger ages, those logistical tasks fall squarely on the coach or a small group of volunteers. The picture that emerges is not of a simple hobby, but of a role that demands time, attention, and emotional energy.

If the paycheck is not the main benefit, what keeps coaches out there season after season? For most, the answer lies in the relationships and in a steady stream of small, meaningful moments that never show up in standings or résumés.

Coaches talk about the joy of seeing a shy player find the courage to speak up, or a child who once avoided the ball suddenly wanting it at their feet. They remember the first time a team put together a passing sequence they had been working on for weeks, or the look on a player’s face when they finally nailed a skill that once felt impossible. These moments anchor the effort and the sacrifice.

There is also a deep satisfaction in walking with players over many years. Youth coaches often see kids grow from uncertain beginners into confident teenagers and young adults. They are there for injuries, tough losses, and difficult choices about school and other activities, as well as for the big wins and milestones. Knowing they played a small part in that journey—on and off the field—is one of the most powerful rewards the role can offer.

For many coaches, that is the heart of the profession: not a career move, but a chance to shape a small piece of a young person’s story. They are not just teaching kids how to dribble, pass, and defend. They are modeling how to handle adversity, how to collaborate, and how to lead and follow with character. When families see and support that reality—from the recreational fields all the way up through the highest tiers—everyone on the field benefits.

Parents are a huge part of whether coaching feels sustainable or exhausting. The same environment that helps kids thrive can either energize or erode the adults who make that environment possible. When families understand the pressures coaches face and choose to support rather than scrutinize from the sidelines, they make it far more likely that good people will stay in the game.

…all ways of saying, “Your time matters.” Civil sideline behavior—cheering for good play, resisting the urge to coach over the coach, and avoiding negative comments about players, referees, or opponents—gives coaches room to do their job and creates a safer emotional space for kids. A coach who doesn’t have to manage constant friction from the stands can focus on teaching, guiding, and encouraging.

Communication is another important piece. Every season will include disappointments: a tough loss, a position change, or less playing time than a child hoped for. How parents handle those moments has a direct impact on the coach’s motivation. Approaching questions calmly, at appropriate times (not right after a game), and from a place of curiosity rather than accusation shows that you see the coach as a partner, not an adversary. When parents assume good intent—“Help me understand your thinking here”—it invites productive dialogue instead of defensiveness.

Gratitude, though small, is powerful. A quick “thank you” after training, a note at the end of the season, or a message highlighting something positive the coach did can carry more weight than families realize. Coaches rarely get formal recognition; most of what they hear are complaints or requests. Genuine appreciation helps balance that emotional ledger and reminds them why their work matters. When a player, especially, expresses what they’ve learned or how they feel supported, it can sustain a coach through many long nights of planning and problem solving.

Perhaps most importantly, kids are watching every interaction between parents and coaches. The way adults talk about the coach in the car ride home, on the sideline, and around the dinner table sends a clear message about how to handle authority, conflict, and teamwork. If children hear constant criticism—“The coach doesn’t know what they’re doing,” “You should be starting over that kid”—they learn to externalize blame and to see adults in leadership as targets rather than partners.

On the other hand, when they see their parents disagree respectfully, ask questions in the right setting, and still support the team’s decisions, they learn something very different. They learn that you can hold standards and advocate for yourself without tearing others down, that it’s possible to balance competitiveness with respect, and that relationships matter even when things aren’t perfect. Those are lessons that carry far beyond soccer—to classrooms, workplaces, and future families.

Don’t miss the latest youth soccer news, player stories, and development tips.

Join our FREE newsletter today and stay connected!

We do not sell or rent your email address to any third parties.